Curiosity, Conversation, and Happiness

The happiest people in the world are the most social. Many of us seek to scratch the itch of happiness that comes from sociality by an addiction to social media – our little pocket size dopamine hitters. However, the little dopamine hits we get from the buzzes and beeps of “likes” does not create the longer-term serotonin in our bodies that is created with embodied synchronous social interaction.

An issue that stands in the way people feeling motivated to just be and interact together is increasing communication anxiety. Even my honors communication students at ASU express nervousness about being in an elevator without their phone, or even calling and talking to a person to order restaurant take-out. When we spend hours online crafting perfectly curated lives and photoshopped selves, there is less time to practice the fine art of conversation.

So what to do? Perhaps one area to seek respite is that we need not worry so much about what we are going to SAY, but rather should be thinking about what we are going to ASK. Indeed, one of the habits of the most empathetic people is their unending curiosity about others. And, the anxiety melts away somewhat when we can consider a conversation as an opportunity to simply learn about others rather than as a dictate to look good or make a point.

The best question askers are vulnerable and willing to learn. Someone who is only trying to prove themselves right will have no problem asking questions. But, beware. People who think they know best cannot even ask the right questions. Asking questions requires close listening to what other people want to talk about, and then encouraging them to say more. Good conversation is not about winning or proving a point, not about discovering weakness in others, but instead about bringing out others’ strengths and understanding why they believe or act the way they do.

A good place to start in conversation, according to Hans-Georg Gadamer is to ensure that the other person is WITH us in the conversation. This could mean lots of things, but for me, it means that we must create relatability. And creating relatability is also about vulnerability. What might this look like?

At school, I oftentimes play a game with others in the elevator with me. Can I create relatability within 15 seconds? Sometimes this means commenting or asking the other about the weather, or the awful parking situation. Other times it means asking, “do you think those orange crumbles on the ground are Cheese-its or Doritos?” In today’s day and age, offering these snippets necessarily also offers the opportunity for me to be rejected or ignored. Perhaps they won’t hear me if they’re wearing headphones, or they will feel irritated that I have interrupted their screen scrolling. And, sometimes that’s the case. However, often, we share a moment of connection, a chuckle, or moment of camaraderie. And, the research shows that even short conversational connections with strangers provides an uplift in our mood.

Another thing to consider that may make conversation less stressful and more inviting is that we do not (and should not) master plan our interactions. We should not think of a conversation as something we conduct. Rather, it’s jazz improvisation. To become good at jazz, we need practice. However, to become a jazz virtuoso, we must also simply listen and let go of the reigns. Where we end up is not so important as the journey.

So, as we find ourselves in the thick of the holiday season, I hope you’ll join me in finding ways that you can create connection and uplift in your own and others lives through those embodied interactions—whether those be in the form of a quick chat with your coffee house barista, or conversationally dancing through questions and curiosities as you visit with friends and family. As you do so, don’t under-estimate the power of food and sharing personal space for making these interactions even more meaningful. Perhaps a potluck or game night is in your future (BeanBoozled is a great one to do with kids)? Or maybe a long overdue skype call with your cousin. If this feels daunting, remember that the most important ingredient for good conversation is curiosity – a childlike skill that only gets more valuable as we age.

Toxic Positivity

Interview with Sarah J. Tracy and Mark Brodie on NPR KJZZ’s “The Show” on how to avoid “Toxic Positivity.”

Click here to listen!

How I chose my academic path, or better yet, how it chose me

Recently I have been asked by several folks why I chose to go to graduate school and/or why I study what I do. I'm not a huge fan of "why" questions and much prefer "how questions" (something that is its own topic in itself, and that I discuss in this video). Regardless, what follows is a reflection on my own journey. I originally wrote it for a book chapter coauthored with Shawna Malvini Redden for Jaime McDonald and Rahul Mitra's kick-ass book, "Movements in organizational communication research". One of the things I love most about this book is that every chapter begins with the authors' stories. This was a brilliant move by Rahul and Jaime, as there's immense value for readers to understand the subjective and contextual factors that motivate and shape ideas and literatures. Knowing such history helps readers to counter-bias and understand why certain issues or paths were taken rather than others. What's more, I encourage people to think about how authors' messy background and humanity serve to shape, constrain, and produce ideas that we might, at first glance, take to be "objective" or "canon." So, here's my journey. What is yours? What are the life paths of your favorite authors?

Sarah’s Academic Journey

Sarah’s Academic Journey

I gulped in several breaths of warm evening air from the penthouse suite balcony. It felt good to escape the air conditioning and drama inside. Gazing toward the glowing lights several miles away, I imagined the Friday night West Los Angeles scene—beautiful people enjoying the beginning of their weekend. My watch read 8:12 p.m. I needed to get my face back together before returning to my current reality: working late, again, in a toxic environment, under deadline.

My boss had made it clear: if I wanted to succeed, not only did my public relations writing need to be impeccable but I also needed to get used to working long hours and towing the line. Further, I had to conveniently look away from coworkers frequently glossing over ethical missteps. One of my senior colleagues called it “dancing.” I called it making things up. I was 22 years old and absolutely miserable.

Just six months earlier, I had been so hopeful and happy. I was serving as guest relations coordinator at my beloved alma mater and had just landed this coveted public relations agency position during the recession of 1993. Sure, I was only making $21,000 a year, but at least someone offered me a job. What’s more, it was for a public relations agency specializing in socially responsible businesses. What could be better?

My university coursework had trained me to write strategic plans, interact with corporate executives, and craft meaningful community events. The actualities of my job stood in sharp contrast: 60-hour work weeks, a demeaning boss, forced cheerfulness, endless faxing, and unrealistic deadlines. I was burned out, exhausted, devastated.

And so, on that penthouse balcony that summer night, I made myself a promise. I would go to graduate school and make it my mission to somehow help organizations be nicer places to work. And I would get myself the hell out of that “socially responsible” public relations agency.

One year later, I was a doctoral student at the University of Colorado-Boulder. Three classes there fundamentally impacted my research trajectory: organizational identification and control by Philip Tompkins, organizational ethics by George Cheney, and emotion and communication by Sally Planalp. For class projects, I learned everything I could about organizational burnout, wrote a case study on the ethical problems of basing public relations on corporate social responsibility, and was introduced to the research of Arlie Hochschild (1983), a sociologist whose writing style, savvy, and interest in emotional labor shaped my career.

Also during this time, my language and social interaction professor Karen Tracy (no relation) took me under her wing to study interactions between citizens and emergency 911 call takers. She was interested in how conversational particulars resulted in calls that were especially rude (Tracy and Tracy 1998), whereas I was intrigued by the ways call takers managed their emotion when dealing with especially frightening, humorous, or irritating calls (Tracy and Tracy 1998).

Two years later, I took a break from my Ph.D. coursework to work on the “Radiant Sun” cruise ship. For 229 days straight, I danced the macarena, chit-chatted, called bingo, told stupid jokes, and mostly kept a smile plastered on my face. I took notes and recorded interviews with the idea that I should analyze the emotional labor on the ship when I returned to graduate school. To my excitement, Stanley Deetz started working at CU-Boulder during my year away, and his mentorship helped me critically analyze emotional control in the closed and surveilled environment of the cruise ship (Tracy 2000).

Deetz’s (1998) critical organizational standpoint informed my dissertation and early career studies of correctional officers’ burnout and problematic emotional construction (Tracy 2004). I paid attention to how officers communicatively managed the monotonous, often degrading, and sporadically dangerous work of being “babysitters” and “glorified flight attendants” for convicted felons (Tracy 2005).

Along the way, I designed and taught one of the first communication courses focused on emotion and organizing. Until that time, with few exceptions, emotion and organization scholars basically ignored one another. To make my point on the first day of class, I asked my students to scan the index of the Handbook of Communication and Emotion (Andersen and Guerrero 1998) for the word “organization” and the Handbook of Organizational Communication (Jablin et al. 1987) for the word “emotion.” Each word was missing from the other book’s index.

Clearly, there was work to be done. Over the next few years, I introduced students to the small but growing scholarship on emotion and organizing. My first doctoral advisee, Pamela Lutgen-Sandvik (2003) wrote her semester-paper-turned-publication on workplace emotional abuse, and from there, we partnered on several studies related to workplace bullying (e.g., Lutgen-Sandvik et al. 2007). This work attracted attention from the media, international bullying scholars, and the organizational communication discipline like nothing I’d written before. However, the process of qualitatively studying workplace bullying coupled with my past research on burnout and emotional labor was itself emotionally exhausting, and I yearned for something a bit more uplifting.

All this time, I had focused on one guiding notion: if I can describe and analyze the problems of emotion in the workplace, then I could help solve these problems and make workplaces nicer places to be. However, focusing on the emotional problems was only half-baked. Studying burnout, emotional labor, and bullying certainly gave names to bad behavior. However, it did not create prosocial emotions in their place.

For organizations to be places where generosity, exuberance, compassion, and healthy relationships thrive, I realized that attention was sorely needed for studying desired and especially humane workplace emotional conditions. Along with colleagues, over the last few years I have turned attention to compassion and organizational communication (e.g., Clark and Tracy 2016, Tracy and Huffman 2017, Way and Tracy 2012) and developed new classes such as “Communication and the Art of Happiness” and “Organizational Emotions and Wellbeing.” I’m indebted to the doctoral students who have collaborated and written emotion and organizational communication related dissertations along the way[i], including this chapter’s coauthor, Shawna Malvini Redden.

You can read more about Shawna's journey, as well as take a peek at our review of emotions and relationships in organizational communication via our chapter linked at the top of this post.

[i] An incomplete list of former doctoral students who have contributed to Sarah’s scholarship and thinking related to emotion and organizations include: Lou Clark, Emily Cripe, Elizabeth Eger, Timothy Huffman, Pamela Lutgen-Sandvik, Jessica Kamrath, Karen Kroman Myers, Shawna Malvini Redden, Robert Razzante, Sarah Riforgiate, Kendra Rivera, Jennifer Scarduzio, Clifton Scott, Sophia Town, Amy Way, and Debbie Way.

A short soliloquy on merit

Soliloquy is a dramatic device used when a character speaks to herself, “relating thoughts and feelings, thereby also sharing them with the audience, giving off the illusion of being a series of unspoken reflections” (Wikipedia).

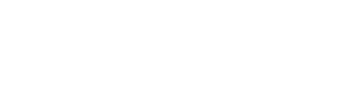

The following is a short soliloquy inspired by Google’s definition of merit and the question of “what = merit”. I wrote it in light of a crisis and awareness of racism in the Communication discipline and the ways that diversity and merit have been framed as antithetical.

The italicized words in the soliloquy come straight from the Google definition. In the soliloquy I am both speaker and listener. Interrogator and discipliner. Betwixt and between. Liminal.

* * * * *

Are you meritorious? Are you excellent? Are you good?

To be meritorious is to be standard. Are you standard? Do you avoid drawing outside the lines?

To be meritorious is to be level. Are you level? For goodness sake, be level-headed, polite, and civil.

If you are not standard and you are not level, you will certainly not make the grade. Better do some extra credit if you ever hope to be worthy.

And take time to account for your virtue. You do want to be virtuous, yes? And praised?

Learn the right forms of virtue and you too may someday be deserving of distinction, worthy of credit, and entitled to eminence.

Just make sure to account for it in standard ways that show your quality. You need to clearly show your caliber in order to receive the right kind of attention.

What? You say you have different values and virtue from the level standard? Quality for you looks different? Your attention seeks non-standard reward?

Hush my darling.

Shhhh… Best keep that to yourself. Or better yet, morph. Simply change thyself.

If not, you may attract the wrong attention, worthy of punishment.

Do you know the people who are arbiters of merit? They get to say whether you are entitled to distinction. Only they have a right to praise you as qualified.

Do you want to earn their approval? Keep leveling. Keep standardizing. Keep accounting.

Someday, maybe, your efforts will warrant deservingness. Someday, maybe, they will achieve the mantel of quality.

Keep striving. Try just a wee bit harder. Because the criteria for excellence, distinction and praise are neutral––based purely on merit.

The communication discipline is bleeding

NOTE: If you want more on the ongoing conversation that my comments are situated within, please explore our colleagues’ commentary on Twitter with hashtag #CommunicationSoWhite, read the backstory of these issues via Mohan Dutta’s astute commentary: https://culture-centered.blogspot.com/2019/06/in-post-made-in-response-to-changes-to.html and examine NCA’s record of documents about the distinguished scholar nomination processes and (lack of systematic) changes https://www.natcom.org/distinguished-scholars?fbclid=IwAR3pvlh-Wf78cbzcesDFSlI2rVi-yKopYlRdtAcMoYzpRK9X1GSUWMb9u0I

The communication discipline is bleeding. Pus oozing. Vomit erupting.

We are suffering.

Most humans turn away from suffering. We build walls on our freeways so we don’t see poverty on our daily commute. We build gates around our communities. We don’t look homeless people in the eye. We conveniently delete, scroll through, or click “sad” or “angry” emojis before quickly moving on.

And, right now, it would be easy, especially for the privileged among us, to turn away from the suffering of our discipline. It’s summer after all. Email auto-replies prove that we are “out of the office”. This is time for family, vacation, and writing!

But this suffering is not suddenly new. It’s been at a slow simmer. Will we ignore this boiling flashpoint?

Of course, only some of us, the privileged among us, have the luxury of ignoring. Or maybe we don’t ignore, but instead treat the situation as perfect summer entertainment. Heck, let’s just get out the popcorn and watch it all go down. Who will be the heroes? Who will be the villains? When will the usual players make their appearance? CRTNET hasn’t been this entertaining for years!

When suffering becomes a drama to be watched from the sidelines, the more vitriol, violence, conflict, and casualties the better. But our colleagues' suffering should not be entertainment.

What if, instead of ignoring or watching as spectacle, we chose to be courageous? What if I chose to be courageous? My coauthors’ and my very own research tells me that the courageous thing to do in the face of suffering is to show compassion.

Compassion comes in the form of recognizing and acknowledging suffering—deeply listening, hearing, and accepting the reality of truths and experiences of those who are suffering. It also means relating vulnerably, which requires us to be open to our own faults and uncertainties—admitting where we have been part of the problem, and choosing to engage in the conversation even if, by doing so, we might engage poorly and sometimes put our foot in our mouth. It means being o.k. when people point out that we did not say things quite right or that our well-intentioned compassion does not result in consequences that actually alleviate suffering. It means being o.k. with hearing that we may have actually made the suffering worse.

Indeed, relating vulnerably takes practice. And anything worth doing well is worth doing badly in the beginning. And after doing it badly, being compassionate (to ourselves and others) means caring less about “looking good” and caring more about (re)listening and courageously trying again.

Finally, and most importantly (and what differentiates compassion from empathy), compassion means acting or reacting in a way so as to materially relieve suffering. Certainly, this may be at the individual level (e.g., sending a supportive note). However, this also comes in the form of transforming structures that result in oppression.

As I have read the recent words from my colleagues of color—among others, Bernadette Calafell, Karma Chávez, Devika Chawla, Amira De La Garza, Mohan Dutta—I am again struck by the immense emotional labor and resilience required to shoulder, resist, and deal with ongoing and ever-present disciplinary structures that say, “You don’t belong here. Get out.” The people in power say, “but we have changed the rules of the game, you can now enter.” And then the powerful seem mystified saying, “Well, we changed the rules so you could enter, and unfortunately not enough people came.” Dragging oneself to the door, to just see it be shut (again), is more than exclusion. It’s trickery. Chicanery.

It’s one thing to be isolated, another thing to be tricked. The first is mean. The second is evil.

People are suffering because the structures of the communication discipline have resulted in evil consequences.

When doors are closed day after day and year after year, it’s not just suffering, but exhaustion and justified outrage. As such, it’s not enough to tweak the rules to the game. It may not even be enough to completely change the rules of the game (which it seems some folks are willing to do). Over time, we need to question the game itself.

Among other questions, we should be asking is this: “What does the institution of distinguished scholars produce at the structural level for the communication discipline?” When I use the word produce, I mean it in the way that Foucault talks about power “producing.” So, I am asking us to consider both intended and unintended consequences.

And, if we cannot come up with good answers, perhaps now is a moment in the discipline when we rise up and say, “new game.”